Welcome to Our Belated Past, your favorite place to connect with the past in a way that’s fun while learning new, off the wall historical stories. Dig into obscure little corners of our collective past to dredge up only the most thought-provoking, engrossing stories. If you like what you’re reading and you want some more, go check out my books!

Philadelphia, June 1737

A prick is a prick. Some things are eternal. Doesn’t matter if it’s 300 years ago or today. They are always the same.

You study history long enough and you realize the ubiquity of certain innate human characteristics. Love and jealousy. Shame and pride. People thinking, feeling the same thoughts. Holding on to the same insecurities that we hold on to today. And sadly just like there are pricks today there were pricks throughout time. Nasty, small-minded, compassionless pricks who looked to exploit the pain of others for their own merriment and mirth.

Which is where this edition of OBP picks up with a group of grown Philadelphian pricks taking advantage of the eagerness of one young man to become a Freemason.

Not to go too into too much detail about Colonial Philadelphia, because there’s a whole book by someone you may know that talks all about it. Wink, wink, nudge, nudge. But the important point to know is just how vibrant a place intellectually Philly was and that is in large part due to the efforts of Benjamin Franklin.

Very few people embodied both the fabled American spirit of a self-made person and a commitment to Enlightenment ideals like creating civic spaces for the betterment and education of his fellow Philadelphians. Real life fruits of his dedication can be found in the building of the Pennsylvania Hospital and the School and College of Philadelphia the future University of Pennsylvania, and other endeavors such as the founding of the Library Company or creating the Junto, an early intellectual fraternal group.

All efforts that either Franklin headed or helped see the light of day and all geared towards promoting knowledge. Given that commitment it is no surprise that Franklin then would embrace Freemasonry for most of his adult life.

Masonry in 1737 was experiencing explosive growth across the globe with reforms made a generation earlier that created the Grand Lodge system and opened up the traditional stone workers guild to more and more “accepted” masons (i.e. non-stoneworkers). Freemasonry took off across Continental Europe and across the Atlantic in the U.S.

Now lodges like Philadelphia’s St. John’s Lodge, founded in 1731, were a place for like-minded men to meet (for no women were allowed in). A stigma still attached to Freemasonry as their series of quasi-secret rituals (if you knew where to look you could find all of the initiation rituals) spooked the general public.

All of this made Freemasonry this mysterious and somewhat dangerous thing, that was also full of the most prominent people in an area.

Which is what happened in the summer of 1737 in Philadelphia. Where you had a young man, and that’s a key component of this tale that’ll be discussed later, pleading with his master/employer to let him become a Mason. It all went horribly wrong from there.

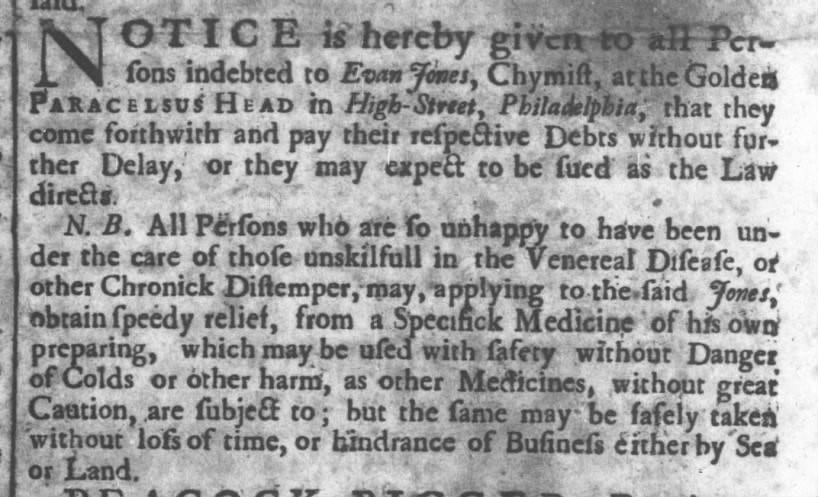

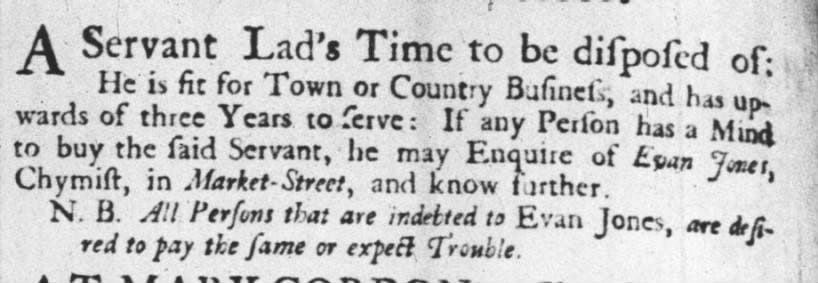

Evan Jones ran an apothecary shop at the corner of Market Street and Letitia Court, where he employed a young apprentice, Daniel Reese (Rees). Jones was a Freemason. One of the early members of the Craft in the city.

Reese, being young and impressionable, desperately wanted to become a Mason, like his master, and so Jones thought it would be funny to put Reese through some made up initiations in order for him to become a “Mason.”

Jones got together with his buddies, John Remington, a local lawyer, John Tackerbury, and an unknown tailor with the initials of E.W. to meet with Reese in Jones’s backyard one night. There they put Reese through a series of increasingly ridiculous trials. This included making Reese pledge an oath of allegiance to Satan. He was made to drink from a “sacramental” cup laced with strong purgatives that most likely made Reese shit and vomit uncontrollably.

As a topper of sorts, instead of kissing a book to swear his allegiance to the Masons, the men had Reese kiss the ass of Tackerbury. With that Reese was made a “Freemason.”

Afterwards there was much amusement at the boy’s expense. Jones began telling the story all over town sharing it with the ideal of “Brotherly Love,” Benjamin Franklin, who admitted “I laugh’d and perhaps heartily” when he heard of Reese’s initiation. Jones continued on relaying to Franklin his plans for the next initiation ritual he planned to put Reese through to elevate him to a higher Masonic degree.

The most damning thing about this encounter between Jones and Franklin was that Ben and Reese had a moment alone together where he did not warn the young apprentice of what they had in store for him or that it was all to be made a butt of jokes, “I was acquainted with, and had a Respect for the young Lad’s Father, and thought it a Pity his Son should be so impos’d upon, and therefore follow’d the Lad down stairs to the Door when he went out, with a Design to call him back and give him a Hint of the Imposition; but he was gone out of sight and I never saw him afterwards; for the Monday Night following, the Affair in the Cellar was transacted which prov’d his Death.”

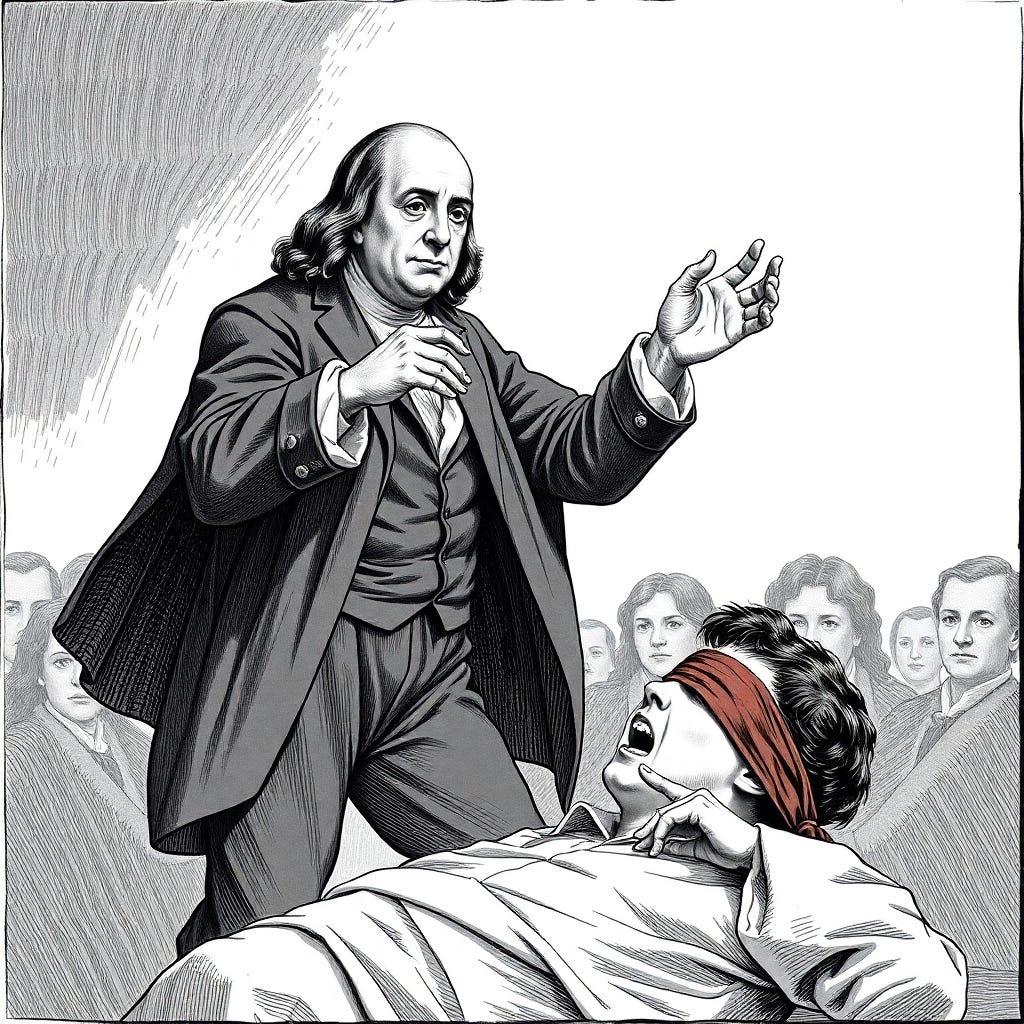

On the night of June 13, 1737, Reese was brought to Jones’s cellar blindfolded with even more men waiting and he made to repeat his dedication and subservience to Satan.

Jones had concocted a game of “Snapdragon,” which did not seem like much of a game at all. It consisted of a pan of camphor with some brandy mixed in set ablaze in order to throw a frighteningly blue flame. Behind the flame stood one of the participants cosplaying as the devil, dressed up with a cowhide draped over himself and a pair of horns to look more Satan-y.

All of this did not have the intended effect. When the blindfold was removed from over Reese’s eyes, he did not react with horror or terror, much to Jones’s chagrin. So Jones decided to up the theatrics, picked up the pan full of burning liquid and approached the still kneeling wannabe Mason.

Now it is not agreed upon if Jones purposefully threw the pan of burning liquid on Reese, if it was an accident, or if one of the other men down in that cellar with him jostled his elbow. There was testimony afterwards claiming all three. Either way the liquid flame flew all over Reese.

Franklin was the only one to provide details of the injuries that Reese suffered, writing, “the Parts burnt, which were from the Breast down to the Thighs, appeared like the Skin of a roasted Pig, varied with several Spots, some black, some of a livid Colour.” Reese held on to life for a few agonizing days, but finally succumbed to his burns later that week.

A Coroner’s Inquest was immediately convened, and they determined that Reese’s death was accidental. Jones, Remington, and Tackerbury were all indicted as a result for manslaughter. They would go on trial early in 1738.

Reese’s death was big news all over the city making the trial must see viewing, and for the 15 hours the trial took place the spectators in the courtroom learned all of the lurid details of Jones and co. 's plan to haze young Reese.

In the end, Jones and Remington were found guilty of manslaughter and Tackerbury was acquitted. Remington appealed for a pardon and received it. Jones' punishment was to have his hand branded to let all others know he had killed another.

Both Remington and Tackerbury seemingly slipped quietly into the shadows of history. For his part, Jones appears to have quit the pharmacy business and moved outside of town to run a farm and a little inn.

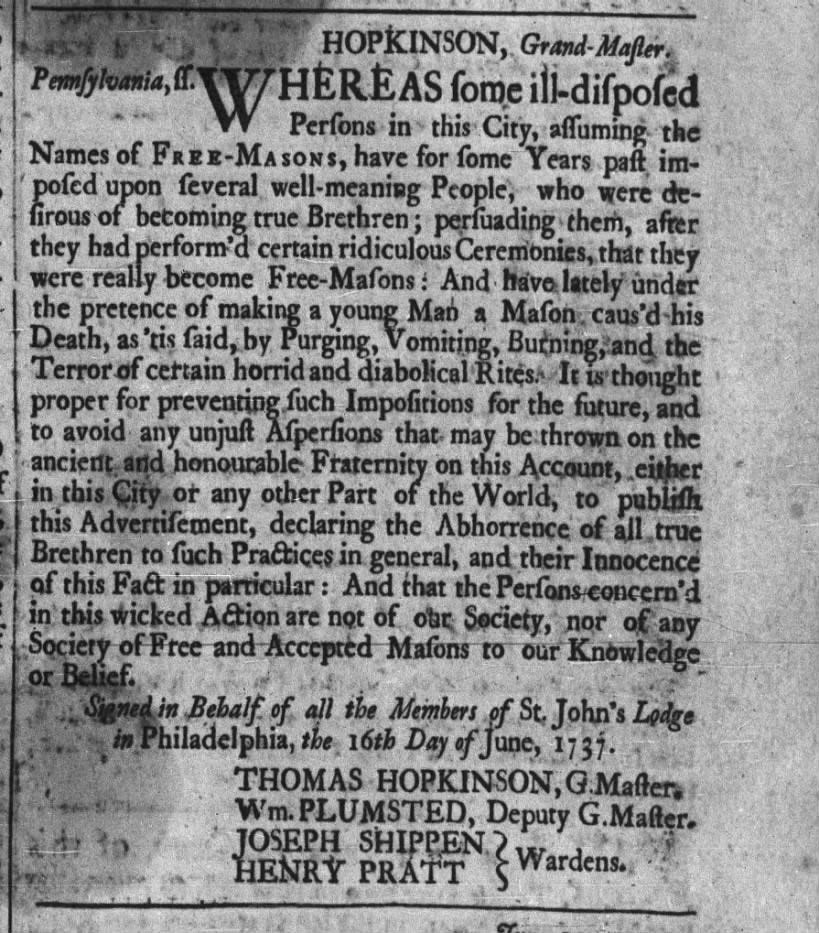

Almost immediately following the incident as the news spread, members of the city’s St. John’s Lodge were quick to publish a notice distancing themselves from Jones.

To show the extent to which Masonry had spread and was accepted by the elite of Philadelphia, those signing this statement were Thomas Hopkinson (prominent figure in the city, who would go on to become the 1st president of the American Philosophical Society and the father of future signer of the Declaration of Independence, Francis Hopkinson), William Plumsted (son of the mayor of Philadelphia and a future mayor of the city himself), and Joseph Shippen (a member of the influential Shippen family).

The statement alludes to this happening before but the previous hazing had not ended in death. This also shows the eagerness of the Freemasons of the city to try to get ahead of the story and distance themselves from any sort of unsavory press. During the trial, it was revealed that Tackerbury had been expelled from the lodge, could it have been for similar behavior?

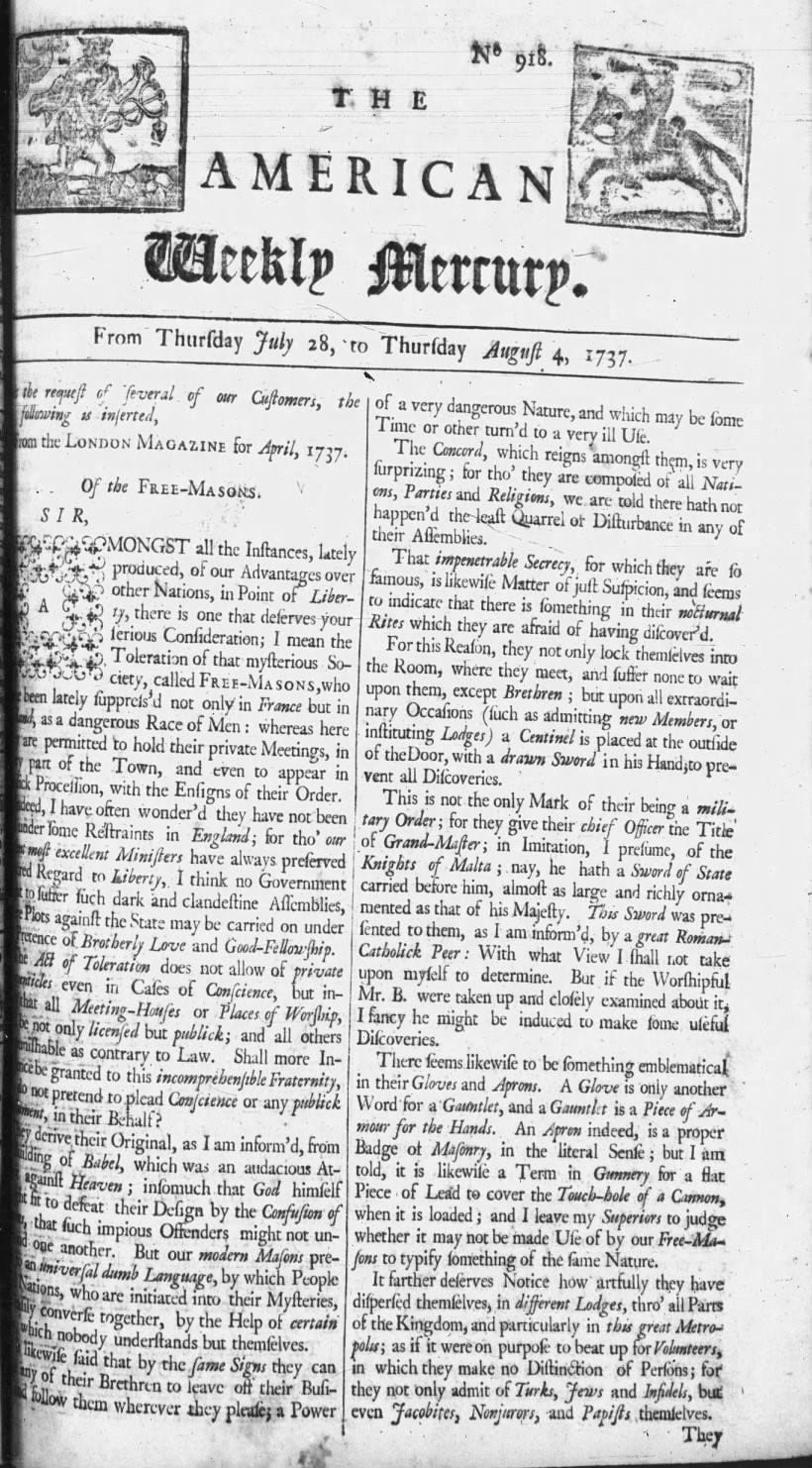

News of the verdict kicked off a brief war of words through Philadelphia’s newspapers, primarily Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette and the rival American Weekly Mercury, published by Andrew Bradford.

Franklin had held his tongue throughout the proceedings, primarily because he was called as a witness, but as soon as it was all over he took to the pages of the Pennsylvania Gazette to publish an overview of the case.

The published piece stirred up the ire of Bradford who roasted Franklin in the Mercury, calling out his hypocrisy throughout the entire affair, “if the kindness [Franklin] expresses to have for the Father, or the Abhorrence of the Imposition on the Son were real, why did he not (since he had several Days opportunity for it) sooner inform the Magistrate, or advise the Young Man, so as to prevent that Imposition, and the unhappy Consequences that happened in the Cellar?”

This left Franklin scrambling to save face, “I was so far from encouraging [Reese] in the Delusion, or taking him by the Hand, or calling him Brother, and welcoming him into the Fraternity, as is said, that I turned my head to avoid seeing him make his pretend Sign, and look’d out of the Window into the Garden.”

So instead of intervening at all Franklin literally turned his back on Reese and the “fun” being held at his expense. It certainly didn’t help his pleas of morality that he had also admitted to having taken the Satanic Oath of Allegiance Reese was made to recite and passed it around to his friends and acquaintances.

Franklin felt most perturbed not by the accusations and scrutiny of his behavior throughout the ordeal, but by his mother learning that he was a Freemason. She was not happy about it at all. Like any dutiful son, Franklin had to reassure her that Masons were “a very harmless sort of people; and have no principles or Practices that are inconsistent with Religion or good manners.”

Franklin makes no reference to this incident in his Autobiography. While the incident didn’t have any lasting impact on his reputation, it did relatively early in his career. It did show that there were those out there who chafed at Franklin’s moralizing and how hollow those words appeared that went into the pages of Poor Richard’s Almanack. Because someone who wrote “A right Heart exceeds all” or “When you’re good to others, you’re best to yourself,” also made fun of a boy who was being cruelly hazed, stood silent when the events that would lead to his death were being discussed, and then go on to insist that when Jones and co. were convicted that they sort have received a harsher sentence.

The great shame of this whole case is that Daniel Reese’s voice has been completely silenced throughout the whole ordeal. Nothing is known of him outside of the events surrounding his death.

Like many victims a lot of the blame was heaved upon his burnt soul. He is called “young and inexperienced,” “simple-minded,” credulous,” and “unsophisticated,” while even the prosecutor referred to the “Lad’s Simplicity.”

While all of this may be true, no one has ever stopped to think why it was so. How could a pharmacist’s apprentice be so “simple-minded” and “unsophisticated”? Well, it’s because in all likelihood that Reese was still a child or at the very best a teenager when all of this was happening to him.

Apprentice was a fancy way of saying that Reese was the indentured servant of Jones. It was common practice for children to be apprenticed out to local tradesmen in order for them to learn that skill to set them up so that they could support themselves as they come of age.

Benjamin Franklin became his printer brother’s apprentice, where he got his first taste for writing and learned how to become a printer himself. His indenture to his brother was to last nine years only for him to cut it short by running off to Philadelphia.

That was the educational system at the time. Where children ages averaging between 12 and 14 would enter into an apprenticeship. These indentures typically lasted between four and seven years.

For their unpaid labor, indentured servants expected to receive job training and a place to stay during what today would be our high school years. The expectations were that servants were to be “justly” and “kindly” treated.

Indentured servitude played a crucial role in Philadelphia’s history, and apprenticeship in general served a key function in the society. As historian W. J. Rorabaugh notes, “[Apprenticeship] was a system of education and job training by which important practical information from one generation to the next; it was a mechanism by which youths could model themselves on socially approved adults; it was an institution devised to insure proper moral development through the master’s fatherly responsibility for the behavior of his apprenticeship; and it was a means of social control imposed upon potentially disruptive male adolescents.”

While none of the reports or information about the case clues us in on Daniel Reese’s age, it is safe to say that he was most likely between 12-20 years old. The best case scenario is that all of this bullshit was being done to a naive young adult. Worst case scenario was that they were torturing a child, which greatly recasts the entire series of events around Reese’s death.

It was a child who was eager to become a member of a secret society. It was a child who Jones and his buddies blindfolded. It was a child who they drugged. It was a child who they made to pledge an oath to Satan. It was a child who was made to kiss the ass of one of the men. It was a child who Franklin let walk out the door without saying anything. And it was a child who Jones spilled/threw burning liquid all over, which led to a child’s death.

The same day the judge handed down his sentence to Jones and his accomplices for the roles they played in Reese’s death, he sentenced a convicted burglar to death while providing Jones a slap on the hand.

Notes on Sources

Perspective on apprenticeship in the Colonial Era comes from The Craft Apprentice by W. J. Rorabaugh and for more on the lives of indentured servants in Philadelphia check out my Raising Philadelphia: The Making of America’s First Great City, 1750-1775. Details concerning the actual case come from the newspaper coverage, most of which was printed in the history of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania’s bicentennial celebration of Franklin.