Welcome to another fabulous edition of Our Belated Past. Your monthly-ish (or whenever I get around to it) dose of historical musings. If you enjoy what you read and want some more, feel free to check out my book, Lemuria: A True Story of a Fake Place, and why not go ahead and preorder my next book due in the fall, Raising Philadelphia: The Making of America’s First Great City (maybe next time Charleston!).

I was all prepared to do an exploration of whether or not John Wilkes Booth was a nepo baby. But two things quickly became apparent as I researched. First, the profession of actors and the perception of them was way different than we think of it today. It was not a glamorous life though still not working in mines, but one of constant touring struggling to make ends meet like most others in the country at the time.

The other thing was that many young actors of the stage were the offspring of actors. Booth’s two older brothers were well-known and respected actors (more so than he was) and many, many others were born into it. Learning the trade by being on tour with their actor parent and exposed to that life from an early age.

Plus, I didn’t feel like writing about that asshole Booth and instead becoming entranced by a little-known story from the investigation into President Lincoln’s assassination. Booth shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre during a production of the play Our American Cousin*, and a week later investigators with the War Department restaging the play at the theater.

*The story behind how Our American Cousin was first produced and its immediate success is a whole other can of worms and worthy of its own TV series.

The inherit drama in this sort of crime scene reconstruction seems more in-line with something out of an episode of Colombo and not so much mid-19th century criminal investigations. The novelty that the investigation took and the degree to which it was carried out were not only rare at the time period, but they are very early examples of injecting scientific methods into criminal investigations, i.e. forensics.

I will not be doing a deep dive into the history of criminology or forensics, but the criminal investigations and the entire investigation around uncovering Booth’s conspiracy are fertile, virgin forests for serious, capital “H”, Historical research. Because they do represent a revolutionary step in investigating crimes. The same sort of steps and actions which would be taken for granted today but were being forged in the moment during the Civil War.

The 19th century was when professional police forces first began to be formed in cities across the world and when baby steps were being taken to introduce modern police practices. After the Civil War, people such as Alphonse Bertillon would develop more modern forensic techniques revolving around the measurements of criminals’ physical features and in the early 20th century fingerprints would first start to be used to help identify criminals.

However, at the time of the Civil War and in America in general, it was a time where science and criminology were not intimate partners. I don’t really want to get into a fully history of forensics, but some levels of scientific methods have been applied to criminal investigations for centuries. With the Chinese from the 6th and 7th centuries providing some of the clearest examples of utilizing the science of their time to solve crimes. But the history of forensics is a rather hodge podge affair particularly in the West with brief dalliances by individuals to apply scientific or basic deductive reasoning skills to solve crimes.

The Civil War served as a major boon for criminology in America. And you can’t have investigations without crimes, and the massive economic buildup to support the war cause created move than enough opportunities for unscrupulous businessmen to take advantage of the lack of oversight.

Almost from the beginning of the war, forensic accounting became a major tool in countering the near endless number of claims of war profiteering coming in. Northern contractors rarely felt any compunction in supplying Union troops with shitty equipment or creating outright fraud. Southern contractors were just as unscrupulous, but overall lack of manpower didn’t provide the opportunities to investigate like there existed in the North.

No area was untouched by the grift going on. Army and Navy. Ordinance and supplies. All of which were used to line the pockets of the contractors, officials, and troops in charge of overseeing the business being done.

The War Department though wasted little time to begin their investigations into the claims of war profiteering. In the summer of 1861, working in tandem with Congressional Committees, the War Department began looking into ordinance contracts collecting thousands of pages of testimony as a result.

Later in the fall of 1862, the War Department began investigating other types of contracts for supplies this time being headed up by my boi, Henry Steel Olcott. H.S.O. is basically the occult Forrest Gump of the 19th century. But for this endeavor, Col. Olcott became probably the world’s first forensic accountant as he investigated dozens upon dozens of cases of malfeasance going on at various levels all over the North.

Olcott would be alerted to a potential new case and get started working on examining the information on hand. Going deep into all of the financial records to ascertain the crimes hidden within them. Here’s an example he provides from his article, “The War’s Carnival of Fraud”, on investigating New York businessman, Solomon Kohnstamm,

Kohnstamm’s crime consisted in his procuring from landlords-generally German saloon-keepers-their signatures to blank vouchers, which he would have filled up by his clerks for, say, one or two thousand dollars each, and then either get unprincipled commissioned officers to append their certificates for an agreed price, or, cheaper still, forge them. By this device he drew over three hundred thousand dollars from the “Mustering and Disbursing Office” in New York, of which sum the greater proportion was in due time ascertained by me to be fraud. The examination of all these accounts was a work of time and laborious and patient research, as may be imagined.

I do imagine so, Henry.

Case after case after case was plopped in front of Olcott and he dutifully went about his business over the course of the remainder of the war investigating these financial crimes. Him and his small team of detectives were so good at this that they were called in to assist in the investigation of the Lincoln Assassination, where they arrested Lewis Powell and Mary Surrat. Olcott acted as a special commissioner for the War Department gathering and organizing the massive amount of evidence that poured in as a result of the investigation into the conspiracy that led to Lincoln’s assassination.

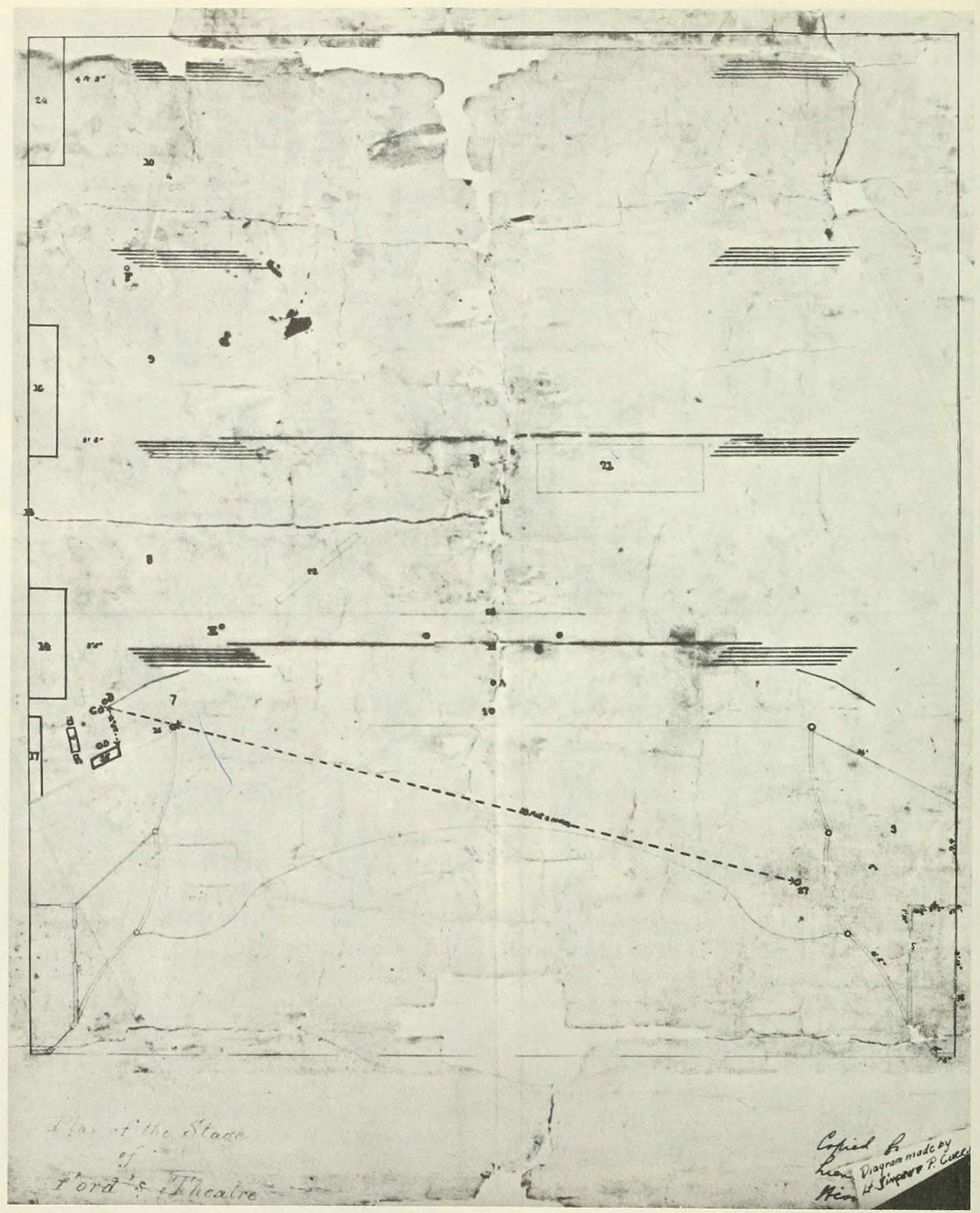

One of which was a report and sketch made by Lt. Simon P. Currier, who was given the task of restaging Our American Cousin to primarily focus on the movements of the actors, stagehands, scenery, and everything going on backstage to see if anyone involved in the production had any involvement in the assassination plot.

So, a little over a week after the assassination, while Booth was still at large, Currier gathered a full cast and crew and put them through probably the longest, most tortured, incomplete production of Our American Cousin that has ever been staged. This included 19 actors and actresses, four sceneshifters, a stage carpenter, an assistant carpenter, property man, a gasman, a backdoor keeper, and a promoter. Twenty-nine persons coming and going on stage and behind it.

Some of the cast from that fateful performance had remained in the city, while the leading lady of the night, Laura Keane, hightailed it out of D.C. only to be detained in Harrisburg, PA for questioning before being released and moving on to the scheduled next step on her itinerary.

The play began. Currier acting as the detective/director. The actors all wore their street clothes since the play’s costumes had been taken as evidence. Currier observed the timing of everything. The movements of each person at every moment of the play, “At every change of scene I had a correct measurement made of the width of the passage between the wings and west wall of the building. This being the passage through which the assassin escaped.”

Currier was determining if and when any of the crew had the most opportune time to create an easier getaway for Booth, “The carpenters and property man have it in their power to obstruct or keep clear the passage to which I have alluded. From the information gathered it appears that this passage was kept to say the least, remarkably clear upon that eventful evening.”

Currier created a sketch of Ford’s Theatre to back up these findings and show where everyone and everything was located at the time of the shooting and Booth’s escape. This is the type of crime scene reconstruction that is common now but was all but unheard of at this time. Due to the magnitude of this particular crime circumstances called for unprecedented steps like Currier’s dramatic reconstruction.

War is often a great incubator, where the necessity supercharges innovation leading to breakthroughs. Most often this has major impact on technology with new weapon systems but also the scientific in the case of the Manhattan Project and the development of the nuclear bomb. However, Currier’s reconstruction and Olcott’s investigations show that innovation occurs even in unexpected realms like forensics.

The direct impact of Currier’s conclusion would be the immediate arrest of Edmund Spangler, the carpenter’s assistant at the theater, for being part of the conspiracy. Spangler stood trial along with the rest of the Booth co-conspirators but was acquitted of the larger charge of conspiracy and directly assisting Booth enter the President’s box but found guilty of assisting Booth in his escape. Spangler received jail time along with Samuel Mudd and both would be pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1869.