The Hoax That Ben Franklin Couldn't Quit

Or the New World Order, brought to you by the Hudson Bay Company

Hey you history lovers!

Here be your bi-weekly(ish) dose of history-related foods for thought. If you happen to like what you’re reading please feel free to leave a comment, email me (contact@justinjmchenry.com), or share wherever you like to share such things.

A little self-promotion. Go check out my recent appearance on the American Hysteria podcast, where I give a rundown of Lemuria. Coincidentally that happens to also be the subject of my forthcoming book, Lemuria: A True Story of a Fake Place. You should probably pre-order it.

For centuries, many chased the fabled Northwest Passage. Expedition after expedition into the chilly waters of northern Canada tried and failed to pick out a navigable route in the miasma of islands and ice floes.

As early as the fifteenth century, explorers prodded for a way through the Arctic in an attempt to dramatically cut down the time it would take to travel from Britain to the Pacific Ocean. This would be something British officials would be chasing well into the 20th Century.

The search for a Northwest Passage also served the background for Ben Franklin to turn into an internet sleuth and stumble upon one of the more quaint conspiracy theories.

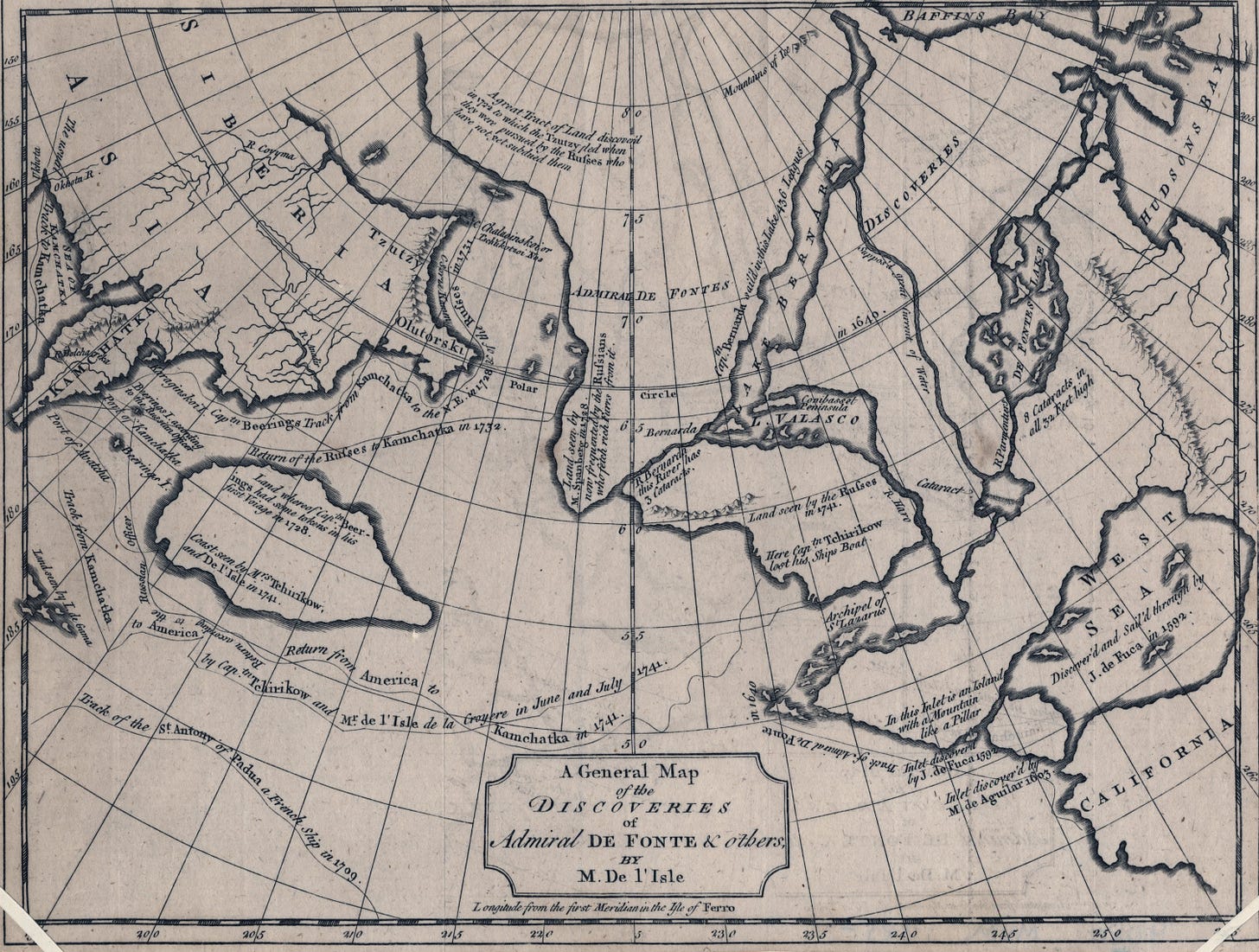

Beginning all with a letter written (ALLEGEDLY) by a Spanish Admiral and “Prince of Chili”, Bartholomew De Fonte, detailing his leading a small armada of ships from South America up the Pacific coast of the Americas in 1640. As they reached the extreme reaches of the Pacific Northwest, De Fonte recounts traveling down a series of rivers and lakes until they reached the Hudson Bay.

De Fonte’s account first appeared in the June 1708 edition of James Petiver’s Monthly Miscellany or Memoirs for the Curious, which is a legit good name for a newspaper. And it is very highly likely that Petiver invented the De Fonte story. Nothing really came of the story though until a few decades later when Irish MP Arthur Dobbs got a hold of it, believed in the veracity of the story, which prompted him to fund an expedition led by Christopher Middleton in 1741 to look for a NW Passage.

Middleton like many others after him came back empty-handed and convinced that a passage did not exist. Dobbs was not buying this and published a book saying so in 1744, Account of the Countries Adjoining to Hudson’s Bay. Where he goes on to accuse the powerful Hudson Bay Company of bribing Middleton and others to hide the fact of a NW Passage in order to protect their monopoly on trade in the area. It really is a great piece of 18th century anti-corporate vitriol:

“The Reason why the Manner of living there at present appears to be so dismal to us in Britain, is intirely owing to the Monopoly and Avarice of the Hudson’s Bay Company, (not to give it a harsher Name) who, to deter others from trading there, or making Settlements, conceal all the Advantages to be made in that Country, and give out, that the Climate, and Country, and Passage thither, are much worse, and more dangerous, than they really are, and vastly worse than might be.”

“[The Hudson Bay Company] have been so base to their Country, as not only to neglect it themselves, but to prevent and discourage any Attempt to find out so beneficial a Passage, and have also prevented any Persons from settling in those Countries…Besides, they have not only neglected to find a Passage to the Western Ocean, but have also refused to look for it, and have discouraged and endeavoured to seduce others from finding it, by offering Rewards or Bribes to Captain Middleton, who was employed by the Government to make that Discovery, as he informed me.”

Throughout Dobbs keeps accusing Middleton of “concealing” and “disguising” the true NW Passage by providing false accounts of tides or frozen straights and other fabrications laid down in his journal. This kicked off a war of words between Dobbs and Middleton with each publishing their own pamphlets bashing the other.

Maybe the biggest strike against a grand Hudson Bay Company conspiracy involving Capt. Middleton was that after his commission was over with the Royal Navy he went back to the Company to request a command from them and they ignored his requests.

Dobbs received aid in his efforts to discount Middleton and the Hudson Bay Company by one of the sailors on the expedition, Theodorus Swaine Drage, who would go by the less regal sounding Charles Swaine, saying that he believed that a NW Passage existed and wrote his own account of the voyage.

Which is where Benjamin Franklin gets involved. He had already shown interest in the NW Passage by publishing portions of Middleton’s account in the 1747 Poor Richard’s Almanack. And had been gifted a copy of Swaine’s book. By this time, Swaine had relocated to Maryland and loaned Franklin his collection of NW Passage materials, which included Dobbs’s book.

This led Franklin to becoming familiar with the De Fonte account, which also led him to turning into boy detective as he started to investigate the claims of De Fonte by focusing on the names of others mentioned throughout.

De Fonte mentions meeting a ship commanded by Captain Shapley and owned by Major General Seimor Gibbons. Franklin was able to confirm that a Major Edward Gibbons once lived in Massachusetts at the time and sailed on voyages. He also found evidence of there being a Captain Shapley who lived in Charlestown. For Franklin, this was all that he needed to prove De Fonte’s account.

And he set about fundraising for another expedition to find the NW Passage to be led by Swaine. After purchasing a sloop, the Argo, Swaine and crew sailed in the spring of 1753 for Hudson’s Bay and the discovery of the NW Passage. They returned later that year with some new information about Labrador harbors, but nothing concerning the passage.

Swaine would lead a slightly more disastrous expedition the following year when three members of his expeditions were killed by the Indigenous population on Labrador. Upon returning the Argo would be sold putting an end to active expeditions into the NW Passage originating from Colonial America.

This however did not end Franklin’s interest in finding the Passage. In 1762, he wrote a lengthy letter to his good, British friend Dr. John Pringle that provides incredible detail about his belief in a NW Passage and the De Fonte account. And as late as 1783 he was boring John Adams with the De Fonte story.

Roald Amundson would be the first to navigate the NW Passage entirely by boat in 1906 and thanks to global warming, climate change, and the continual melting of Arctic ice the Passage is more navigable than ever. You can even take a cruise through the Passage. Hudson Bay Company be damned.

References:

Percy G. Adams. “Benjamin Franklin’s Defense of the De Fonte Hoax”. The Princeton University Library Chronicle. Vol. 22, No. 3, Spring 1961. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26402975

Arthur Dobbs. Account of the Countries Adjoining to Hudson’s Bay. 1744. https://archive.org/details/accountofcountri00dobb_0/page/85/mode/1up

Benjamin Franklin. “Letter to John Pringle”. May 27, 1762. Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-10-02-0046

Joseph A. Leo Lemay. The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 3, Soldier, Scientist, and Politician, 1748-1757. 2009.